Edward Flanagan – The Heart of the Shepherd

Talk by Bishop Kevin Doran at Father Flanagan Conference

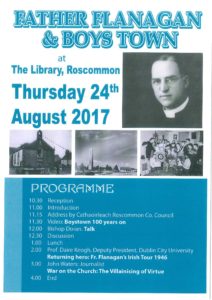

Roscommon Library, 24th August 2017 as part of Heritage Week

Over the past few years, since I came to the Diocese of Elphin, I have been surprised at how few people know about Fr. Edward Flanagan. Perhaps I shouldn’t be all that surprised because, although I had seen the Spencer Tracey movie, I knew relatively little about Fr. Flanagan myself, up to three years ago.

I welcome the opportunity to participate in this Conference which is intended to make him better known.

Others will speak of Fr. Flanagan the founder of Boystown, or Fr. Flanagan the educationalist. I won’t ignore those things, but my particular interest this morning is in looking at Edward Flanagan as a child of our Diocese, who – unknown to himself – set out in 1886 on the path to holiness.

In these days leading up to the All Ireland finals, we probably need – first and foremost – to tackle the question of whether Edward Flanagan was a Roscommon man or a Galway man. I think we have to acknowledge that it is a draw. It is undeniable that, since he was born in Leabeg, he is in civil terms a Roscommon man. On the other hand, his parish is Ballymoe which is in Co. Galway. So from a Church point of view he is a Galway man. I’m not sure how the GAA would call it, and his primary school at Drimatemple is variously described as being in Ballymoe, Co. Galway or in Castlerea, Co. Roscommon. I’m personally happy to claim him as an Elphin man and to acknowledge him as a citizen of the world.

Infancy and Childhood

Edward Flanagan, as many of you know, was the eighth of eleven children born to John and Nora Flanagan. They were a hard-working farm family and, if you have ever visited the remains of their home in Leabeg, you will know that there was probably relatively little to set them apart from their neighbours. We go to great lengths these days to insulate our homes, to protect ourselves from the damp, and to keep ourselves warm. Things were different then and Edward, who was very frail as an infant, only survived because of the quality of care that he received from his parents and grandparents.

The care that Edward received from his family was not limited to keeping him warm and well-fed. He was also nourished with the faith of hard-working and deeply religious parents. That is not to say that they were pious, but that there was a clear place for God in their lives. Faith was on the agenda. From his father, Edward heard stories of adventure; stories of the struggle for Irish freedom and the lives of the Saints. He also tells us: it was from his life I first learned the fundamental rule of life of the great Saint Benedict, ‘pray and work.’ ”

If you read the story of King David, in the Old Testament, you will find that he was the eighth son of Jesse. When the prophet Samuel came to anoint a new King for Israel, David was out in the fields minding the sheep. He wasn’t even considered, until Samuel, inspired by God, asked for him to be sent for. He went on to become the great Shepherd King of Israel. Edward describes himself in one of his letters to an old friend as “the little shepherd boy who took care of the cattle and sheep”. He says: “that seemed to be my job as I was the delicate member of the family and good for nothing else”. Yet, like King David, I suspect that it was in tending the sheep around Leabeg, as well as in the regular routine of family prayer, that Edward began to develop the heart of the Shepherd.

Priesthood

It is worth exploring briefly Edward’s journey to priesthood, because it was as a priest that Edward carried out the great work which he undertook in Boystown and around the world.

While it was to the Diocese of Omaha, Nebraska that Edward belonged as a priest, his vocation to priesthood was the fruit of the faith which came from his family and from his parish community in Ballymoe. I spoke about this during the celebration of Confirmation in all our parishes this year. The young Edward sat in his seat in St. Croan’s Church, Ballymoe waiting for the bishop to come for his Confirmation. Neither he, nor anybody else in the congregation that day, had any idea as to how the Holy Spirit might work in his life.

Following his secondary education at Summerhill College in Sligo, Edward left with his sister for the United States, where he decided to follow in the footsteps of his brother and to become a priest. The bad health that He had experienced in childhood took its toll on Edward during his years of formation for priesthood. It takes a certain amount of Courage to go back to seminary for the second time, but it is hard to imagine having to return for the third time, after two bouts of serious illness. Edward studied in three different seminaries in three different countries, two of them in Europe while these countries were at war. Courage is one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, which he would have received at his Confirmation.

At this point, I think it is worth putting Edward’s priesthood in a historical context. In terms of the history of Omaha and the United States generally, Edward was ordained at a time when the industrial revolution was in full swing. With the advent of mechanisation, Capital began to take priority over Labour. Profit took precedence over people. Many workers were exploited for low wages and many more no longer had any employment. The tornado which, in the early months of Edward’s priesthood, wreaked havoc on the city of Omaha, served only to worsen the situation, leading to significantly higher levels of unemployment and homelessness.

In terms of Church history, it is worth noting that, in 1891, Pope Leo XIII had written his encyclical letter “Rerum Novarum” which was a critique of both the industrial revolution and the response of Marxist socialism. It called for the state to exercise its responsibility in vindicating the rights of workers. This was the beginning of what, nowadays, we refer to as the Social Doctrine of the Church. It think it is reasonable to see all of this as part of the backdrop to the formation, ordination and early ministry of Edward Flanagan. It might explain to some extent why he was not prepared to stay quietly behind the altar rails, but rather saw it as part of his responsibility, precisely as a priest, to engage himself actively in the care of the homeless, and subsequently of homeless children.

Personal Philosophy:

The personal philosophy which motivated Edward Flanagan in his mission to young people is easy to find in his own writings and in his own engagements with institutions in the US, in Europe and Asia and indeed here in Ireland. One element of that philosophy is his fundamental belief in the goodness of every person.

In a world which is full of suspicion and mistrust, even among colleagues and within families, this willingness to search out and to recognise the good in everybody, is a rather unique characteristic. Fr Flanagan insists that “there is no such thing as a born bad boy.”[1] Firm in the conviction that one must hate the sin but love the sinner, he is convinced that there “are delinquent environments but never delinquent boys.”[2] I don’t believe that it was just naïve optimism, but rather that it was a conviction rooted in his belief that every person is created in the image and likeness of God. People laughed at him then, and I’m sure that some would laugh at him now. He understood well that young people have to be made amenable to the standards of civilsation, but he simply believed that the problems caused by juvenile delinquency could not be laid entirely at the feet of young people themselves.

I think we have to acknowledge that modern society, notwithstanding its elaborate penal system has not solved the problem of juvenile delinquency, or of the fact that troublesome young people often become involved in gangland criminality. Neither can we deny the reality that prisons here in Ireland as in the United States tend to be occupied primarily by people coming from difficult backgrounds. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they are the only ones to commit crime, but it does mean that society tends to be less tolerant of crime when it is committed by the poor, the migrant or those who are less well educated.

Fr. Flanagan’s belief was that the most effective power for change was the power of love. On numerous occasions, Fr Flanagan returns to the idea that in the family or in society, in the home or in an institutional setting, the tool to be used for forming young minds and hearts in the ways of goodness and right relationship is that of love. For him, “where love abides, the answer to all of the problems confronting adults and children is ever present.”[3] He is quite clear: “I do not believe that a child can be reformed by lock and key and bars, or that fear can ever develop a child’s character.”[4] When corrective methods for the delinquent are severe they tend to “break the spirit of youth.”[5] At odds with many of the dominant approaches of his day, he insists that “Physical punishment is destructive – it relies upon brute force instead of appealing to reason and Christian charity.”[6] This was the guiding principle of his approach to intervention and reform at Boy’s Town where it was his belief that “Love not force is the motivating influence in building for citizenship”[7] This is not to say that he advocated a “soft approach”. Love has to be honest and, quite often, challenging.

A third aspect of Fr. Flanagan’s vision of the human person was his belief that we are created for relationship with God and that it is only in God that we find our own true peace, or that we have the possibility of building a good and peaceful society (what in more recent years would be described in the social teaching of the Church as a “civilisation of love”). He insists that “every child should have the opportunity of religious training and development.”[8] He held firmly to the belief that “if they are taught to love God, they will surely become good”.[9] He believed, therefore, that moral training should be built upon the firm foundation of religious education, because morality is an expression of love and “God is love”.

One of the scourges of our time is religious fundamentalism, which is rooted in a false sense of God. I think Fr. Flanagan certainly held the view that most Christians hold, namely that the best way to God is through Jesus Christ. But his image of God was of a loving Father. It would be foolish, I suppose to expect that he would have a post Vatican II view of the Church in the Modern World, but he did acknowledge that every person (and therefore every child) has to find his own path to God. Speaking of prayer, for example, he says, “Every boy should pray, but how he prays is up to him”. In arguing for the place of religious education in society, I believe that Fr Flanagan was simply making the case that people will really only find their way in life when they recognise God is the one who gives meaning to everything and God is the ultimate end towards whom every human life is directed.

Is Fr. Flanagan a Saint?

As most of you will be aware, the Church is currently seriously considering the possibility of proclaiming Edward Flanagan a saint. This is a process which can take many years and, of course, many very good and holy people are never publicly recognised as saints. Usually, if a process for canonisation begins, it is because of a widespread belief among the faithful that a particular man or woman is a saint. The local bishop then begins an in-depth exploration of the person’s life. Evidence is taken from witnesses and the person’s writings and activities are examined for signs of authentic holiness. Once again, I think it is important to say that to be holy is not necessarily the same as being pious; to be holy is to be dedicated to the service of God. The purpose of the preliminary process ihe cause of canonisation is to demonstrate that this is truly a virtuous person.

In Fr Flanagan’s case this process was initiated by the Archbishop of Omaha, because that is the Diocese to which he belonged as a priest. In 2015, the local process was concluded and the Archbishop and his theological commission were satisfied that there was good reason to believe that Edward is indeed a saint. What would have led them to that conclusion?

I have often said to young people preparing for Confirmation that a saint is usually a person who lives a life of prayer and care. There is ample evidence that Fr. Flanagan was indeed a man of prayer and that he never allowed the business of his day to get in the way of the time He spent in the presence of God. He encouraged others to pray, not just by his words, but by the witness of his own life. Prayer drove him out to care, first of all, for the homeless and then for the street children. That active service often drove him back again into prayer. The balance between prayer and care is like the action of the waves on the seashore. They can’t go out unless they go in and they can’t go in again unless they first go out.

Another Christian virtue that we see in Edward Flanagan is the same courage that allowed him to deal with ill health in his youth. When people said he was crazy to be bothering himself with delinquents, or questioned whether such work was appropriate for a priest, he stood up to them. In my own experience, people who have had to struggle against adversity in their own lives either become angry and bitter or, out of their own experience, they develop a real compassion for others. Fr Flanagan was a man of deep compassion and it was that compassion the led him to be critical (and some would say, over critical) of institutions which, in his view failed children. It is important to say that being a saint is not in itself a guarantee that one never makes a mistake. Indeed, it is sometimes said that those who never make mistakes have probably never made anything else either. The virtue of Edward Flanagan would be in the fact that, his motivation was always pure, in the sense that he had only really one desire, and that was to reach out to young people and lift them up, until they could stand on their own two feet and make their own contribution to society and to the Church.

Early in 2017, the Holy See found that the Diocesan process was valid and so the cause for Edward’s canonisation is now being considered in Rome. One consideration will be the careful examination of any alleged miracles which are attributed to Fr. Edward. It is important to understand that this is not about magic. A miraculous cure, for example, would be a cure for which no scientific explanation can be found. Alleged miracles would be examined even by doctors who are not Christian, in order to avoid any suggestion of bias. Jesus, in his own life-time, worked miracles, not to show off how great he was, but in order to put flesh on the compassion of God. The Church has always believed that the compassion of God continues to work through the saints and that, even after they have died, God continues to allow his power to work through them, for those who ask their help. A miracle would be regarded as a sure indication that a person is very close to God.

If the Church declares Edward Flanagan to be a saint, it is not like giving him a knighthood or some other honour. The Church canonises saints because they have the potential to inspire others by their example of holiness. That is why we ask children to take a saint’s name at Confirmation. That is why we might encourage people to read the lives of the saints (provided they are well written and rooted in reality).

What is Edward Flanagan’s relevance for today?

It is worth asking ourselves, as we draw to a close, what might be the relevance of Edward Flanagan as a saint in today’s world. I would suggest that there are probably quite a few ways in which the life of Fr Flanagan might have a prophetic impact in our own times.

- The fact that Fr Flanagan’s contribution to society and to the welfare of children was made as a Catholic and as a priest and was clearly motivated by the experience of God’s love in his own life, bears witness to that fact that the active engagement of people of faith in society is not only perfectly valid but also very necessary. Faith contributes to good citizenship.

- Fr Flanagan’s life is a testimony to the things that can be achieved by generous and hard working volunteers and he would probably question a society in which people seem to accept that nothing can happen without state funding or state control

- Fr Flanagan’s work for homeless young people would challenge a society which builds office blocks while children live with their parents in emergency accommodation or on the streets, or a society in which children are condemned to live indefinitely in direct provision centres, where they have no space to call their own and no opportunity to live a normal family life.

- Fr Flanagan’s life challenges us to look again at the role of parents in handing on the faith to their children and to ask ourselves why we tend to leave that exclusively to teachers.

- Fr Flanagan’s life invites us to explore how our relatiinships in the family, in the workplace and in society, might be enriched by the transformative power of love and by the recognition of the innate dignity of every person as a child of God

- Given his respect for the young people with whom he lived and worked, I am certain that Fr. Flanagan would stand shoulder to shoulder with those who seek to protect unborn children from any ideology that would see them as disposable for any reason.

Ballymoe and Fr Flanagan

Saints, like official reports, should not be left to gather dust. If Fr Flanagan is beatified or canonised in the coming years, that might be seen as the end of a process, but it is only the beginning of a journey. I would want the people of our diocese and of our country to be inspired by Fr. Flanagan and to learn from his example. For that reason, the Diocese of Elphin is supporting the development of a Fr Flanagan Pilgrim Centre in his home parish of Ballymoe. This has already begun with the development of a memorial garden. It is hoped that, in the near future, we can begin transforming the old parochial house into a visitor’s centre. This is our small contribution to keeping alive the legacy of Fr Flanagan in his home parish. In this centenary year of the foundation of Boystown, I trust that his life will become better known, especially here in the Midlands and West of Ireland, where he was formed in faith and helped by love to develop the heart of a shepherd.

[1] Catholic Shimbun 2/05/47

[2] Sekai Nippo 26/04/47

[3] 08/20/46: Letter of Fr Flanagan to M. Immaculate

[4] 12/16/46: Statement of Fr Flanagan regarding article in American Weekly

[5] 12/13/46: letter of McKillop to Fr Flanagan

[6] October 1946: Speech/Article by Fr Flanagan on Visit to Ireland

[7] June 1946: Outline of Speech for Ireland

[8] 09/07/47: Child Welfare Report (Japan and Korea) by Fr Flanagan

[9] 05/02/47: Article Catholic Shimbun